DISCOVER LA OROTAVA

Historial Background

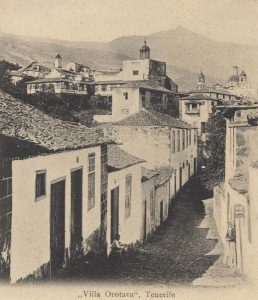

Villa de La Orotava is the only town in the Canaries with an almost entirely intact historical centre, offering comforting walks by its streets. In the town, history meets the visitors and especially the foreign visitors who have wandered by its streets for many centuries, leaving behind some of the most beautiful pages of travel literature. In this sense, it is difficult to find a city of our archipelago that has received more enthusiastic testimonies. However, none of these narratives or the most beautiful stories of literary fiction are as fascinating as the very reality of Villa de La Orotava, a true jewel for those who love art, beauty and history.

Its history begins when the kingdom of Taoro or Tahoro, the richest and most fertile area of the island and perhaps the largest of the nine zones in which Tenerife was divided, was distributed by the crown among the conquerors and their aides for their deeds on 5th November 1496, the year when the conquest was completed. It occupied the extension of the current municipalities of Puerto de la Cruz, La Orotava, Los Realejos, La Victoria de Acentejo, La Matanza de Acentejo and Santa Úrsula. It was the richest and most powerful Menceyato (aboriginal political division of the land with a Mencey as the main ruler) on the island. Here the conquest of Tenerife and, therefore, also of the Canary Islands ended, when the courageous Bentor committed suicide after being defeated by the troops of Alonso Fernandez de Lugo. But the best-known and most famous Mencey was Bencomo, the most powerful and brave of the Guanche (name of the Tenerife aboriginals) Menceyes, from the valley of Arautapala in Taoro, killed in the battle of Aguere and leader of the aboriginal resistance against the invading Castilian troops. Taoro is also a name that the Orotava valley, as well as this region, receives.

The new settlers immediately acquired all the rights to receive the profits generated and began the process of occupying the place, being this fact the origin of the municipality. They proceeded to the distribution of land and water among the men who had participated in the endeavour of the conquest and subsequent colonization: hidalgos (Spanish nobles), relatives of the Adelantado (Spanish dignitary) and creditors of the war feat. The distribution was carried out on 1st January 1502, being the most outstanding one by the large number of beneficiaries. The settlers benefited from the precious gift of water and with an uneven land that allowed them to easily use it for irrigation, as a hydraulic force to move the mills and as a driving force to establish sugar mills. Sugar was a very demanded product in the international market, and this fact, among other reasons, promoted the European expansion by the Atlantic territories as a mean to obtain it. Therefore, the owners of the sloping fertile land of La Orotava valley began to exploit it economically with the cultivation of sugar cane. Those who engaged in its cultivation were rewarded with more plots of land. Even those who declared that they were going to establish a sugar mill were supplied with more than twice as much land. Three sugar mills were established, under the direction of the Portuguese coming from Madeira, brought due to their knowledge of the trade. They worked together with the labour of black people, mulattoes, Berbers, and Guanches.

The new settlers immediately acquired all the rights to receive the profits generated and began the process of occupying the place, being this fact the origin of the municipality. They proceeded to the distribution of land and water among the men who had participated in the endeavour of the conquest and subsequent colonization: hidalgos (Spanish nobles), relatives of the Adelantado (Spanish dignitary) and creditors of the war feat. The distribution was carried out on 1st January 1502, being the most outstanding one by the large number of beneficiaries. The settlers benefited from the precious gift of water and with an uneven land that allowed them to easily use it for irrigation, as a hydraulic force to move the mills and as a driving force to establish sugar mills. Sugar was a very demanded product in the international market, and this fact, among other reasons, promoted the European expansion by the Atlantic territories as a mean to obtain it. Therefore, the owners of the sloping fertile land of La Orotava valley began to exploit it economically with the cultivation of sugar cane. Those who engaged in its cultivation were rewarded with more plots of land. Even those who declared that they were going to establish a sugar mill were supplied with more than twice as much land. Three sugar mills were established, under the direction of the Portuguese coming from Madeira, brought due to their knowledge of the trade. They worked together with the labour of black people, mulattoes, Berbers, and Guanches.

Gradually, the nucleus of Villa de La Orotava was configured as an expression of varied human activities, where the social classes were spatially delimited and socially hierarchical. The nobles, who were the beneficiaries of the Adelantado’s share, occupied the apex of the social scale and resided in Villa de Abajo (Lower Village), the heart of the future city. The most proud of them, of clear aristocratic mentality, will form a closed group in the following years, known as ‘Doce Casas’ (Twelve Houses), which in 1560 constituted a Confraternity. Then we found the craftsmen, the lower classes, emigrants and peasants, who lived in ‘Villa de Arriba’ (Upper Village) or ‘Farrobo’, mostly in houses provided by the gentlemen for whom they worked. We are in the origins of the urban structure of La Orotava municipality. Lastly, above the urban space, was the area inhabited by the poor peasants who lived in stone haystacks, on clay floors and with pine-needle or straw ceilings. According to Leopoldo de la Rosa, the number of inhabitants in 1506 ranged from 80 to 100. When in 1561 the Tenerife census was made, Villa de La Orotava had a population of 526 neighbours in the main urban nucleus, with a total of 2,575 people in the whole area.

The sugar production gave way to the vine in the second half of the sixteenth century, whose cultivation was also encouraged in the distribution of land. In the 17th century, Villa de La Orotava, and the valley that bears its name, was marked almost entirely by wine production, not forgetting that Villa de La Orotava not only worshiped its wines, but also the water, that basic natural resource of great importance for its economy. Two types of wines, considered to be the best of their kind, were harvested mainly in La Orotava valley and in the north-west of Tenerife (Buenavista, San Juan de la Rambla and the Daute region): malvasía and Canary sack. They were bought by the Dutch and English merchants and exported to Europe, mostly to England, the main consumer, from the Garachico port and La Orotava port, now Puerto de la Cruz, the most important one on the island, where there was a small English settlement, together with an English consulate. In those years, this port was an open gate through which the European culture of the time entered the island.

It was in the 17th century when Villa de La Orotava acquired real prominence and economic prosperity as a result of wine production and trade, and underwent an extensive socio-economic transformation. As a consequence of the richness and importance that it acquired, the local elite obtained the emancipation from the city of La Laguna by Real Certificate of the King Felipe IV on 28th November 1648, not without the absence of certain tensions. It also obtained the title of exempt town, becoming the only one in the Canary Islands that had this institutional and honorific title granted by a royal order. This honourable recognition would be filled at the threshold of the twentieth century, exactly on 15th February 1905, with a new royal bestowal, the coat of arms for La Orotava, which was accompanied by the distinction of ‘Very Noble and Loyal Town’ granted by King Alfonso XIII. From then on, it would have its own ‘alcaldes mayores’ or ‘tenientes de corregidores’, political titles with functions as mayor and judge. The new administrative and legal situation provided more economic progress for the town. Population growth is a consequence of this progress. The Canary Islands bishopric’s register for the year 1675 indicates that there were 1,582 houses in Villa de La Orotava and a total of 5,782 inhabitants and there were 368 houses and 2,085 inhabitants in its port.

The dominant group of citizens favoured the construction of convents for the establishment of religious orders, of the Baroque Mother Church of Inmaculada Concepción (Immaculate Conception) and of a refined Canarian and Renaissance architecture with houses and mansions with large gardens, notable facades and stone coats of arms that marked the lineage to which their owners belonged. The Farrobo area managed to have its own church, the San Juan (Saint John) Church, although due to lack of income and resources, works took a long time and it was not finished until the 18th century. The result of this trend was the formation of a city of great visual beauty.

Villa de La Orotava begins to offer a lustrous image that has its correlate in its enchanting green valley that extends from the mountains to the shores of its Atlantic coast, watched from high above by the volcano Teide. It aroused the admiration and glowing praise of travellers, sailors and naturalists born on the island or coming from distant lands, among other reasons, because the mount served as a beacon for seafarers along the coast of Africa at the beginning of the European Atlantic expansion and later on their route to the South. Mount Teide was considered the highest mountain on Earth until the first decades of the eighteenth century and as such has had a significant meaning in Villa de La Orotava. A tradition had been born among travellers and sailors, who included the Peak of Tenerife, among those natural places and phenomena loaded with legend, symbolism and admiration, making it become the icon par excellence of the Canaries. Practically throughout the eighteenth century, much of the life of the town revolves around Mount Teide. It is a source of sulphur that is exported to the Iberian Peninsula, it supplies ice to the island’s upper classes and it is the economic resource of many peasants who acted as guides for hikers in a century marked by an economic crisis.

Indeed, the restrictions imposed by the Andalusian monopoly on trade with Spanish America, the prohibition of direct trade with the English overseas colonies decreed in England in 1663, and the advantages accorded by England itself to Portuguese wines, provoked a serious crisis, being more acute in Tenerife due to its strong dependence on vine. However, the large tracts of land, the fortunes of previous decades and the elegant European culture of its elites allowed the town to continue being a privileged economic and cultural centre. And wine, although it no longer had the importance of old times, remained the basis of the economic and cultural power of the local oligarchy.

In the nineteenth century two of the most relevant events of the contemporary history of the town took place, which would decisively transform villa de La Orotava and its surroundings. The first one occurred at the beginning of the century. In its first decades, supporters of economic liberalism who were against the privileges and immunities that hampered the increase in production and the distribution of wealth, began to carry out the process of disentailing the properties of religious orders and communal lands and definitively abolish the “mayorazgo” (an institution of the old Castilian right that allowed to maintain a set of properties linked to each other in such a way that this link could never be broken). From then on, the economic role of the nobles, although they maintained a very important social power, decreased. Properties began to be disposed of and redistributed. The Church, the municipality and the great aristocrats had to share their fortune with new landowners, the agrarian and commercial bourgeoisie, creditors and other social groups. A process of alienation of goods from private hands, which was accentuated a few years later by the economic crackdown following the collapse of the mealybug market, based on an insect that was bred in cactus to obtain colourings, and whose exploitation had replaced the vine from the thirties to the first lustrum of the eighties.

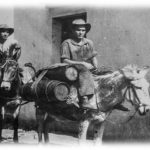

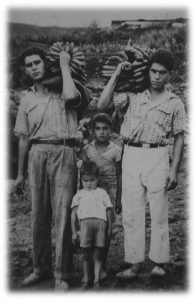

The second event occurred at the end of the century, with the introduction of banana plantations. Bananas came to substitute the ephemeral period of mealybug exploitation and soon became the true export monoculture in the Canary Island’s economy. As the best lands for their production were the ones rich in water, the owners of the Orotava valley decided to introduce this harvest. The initiative was favoured by the presence of the British companies Fyffes Limited and Yeoward Brothers. This agrarian product generated a lot of wealth for the entrepreneurs of the Orotava valley, and in particular for those of the town, who, in large numbers, wisely rented or sold the land and sometimes compromised the totality of the production to the British companies, that were in charge of exporting the fruit. The most important markets were mainland Spain, Belgium, England and Germany.

The second event occurred at the end of the century, with the introduction of banana plantations. Bananas came to substitute the ephemeral period of mealybug exploitation and soon became the true export monoculture in the Canary Island’s economy. As the best lands for their production were the ones rich in water, the owners of the Orotava valley decided to introduce this harvest. The initiative was favoured by the presence of the British companies Fyffes Limited and Yeoward Brothers. This agrarian product generated a lot of wealth for the entrepreneurs of the Orotava valley, and in particular for those of the town, who, in large numbers, wisely rented or sold the land and sometimes compromised the totality of the production to the British companies, that were in charge of exporting the fruit. The most important markets were mainland Spain, Belgium, England and Germany.

The new linkage of Villa de La Orotava with the banana plantations originated great riches among the agricultural proprietors, which allowed them to incorporate a historic eclecticism in architecture. The traditional Canarian household, the renaissance and baroque designs were followed by the modernist, eclectic and neo-gothic styles that began in the last decades of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The town acquired a certain European air.

The banana plantations also greatly favoured the landscape as they reinforced the greenery of the valley and its agrarian nature. The ‘language of the greenery that characterizes the writing of the valley’, using a literary figure, was transformed and entered a new aesthetic phase. The close link between wine production since the 17th century and banana production since the end of the 19th century, that is, the decisive forces of the rural economy, have shaped Villa de La Orotava over the centuries. Today, it is a surprise for the visitor. Entering it means going back centuries in time. The art present in its urban centre, the churches, the convents, the mansions of the aristocracy with their coats of armour and the traditional architecture with its balconies and wooden work, make of it a harmonious, perfect and beautiful place with aged air. When walking along its streets we cannot fail to perceive the fragments of its historical past. All of it extends under the watchful eye of Mount Teide, a remarkable element in the landscape, that also provides the coloured sands and ashes for the tapestry of the Town Hall square in the celebration of the Corpus Christi, one of the artistic jewels of the town.

Villa de La Orotava, with a population of 42,929 inhabitants in January 2015, continues to maintain a basic economic activity focused on agriculture and services. However, its attractive urban centre, its history and its legend make thousands of tourists come to visit it every year to enjoy one of the most attractive towns of the Canaries.